This article was originally published in Italian on Nerdgate.it

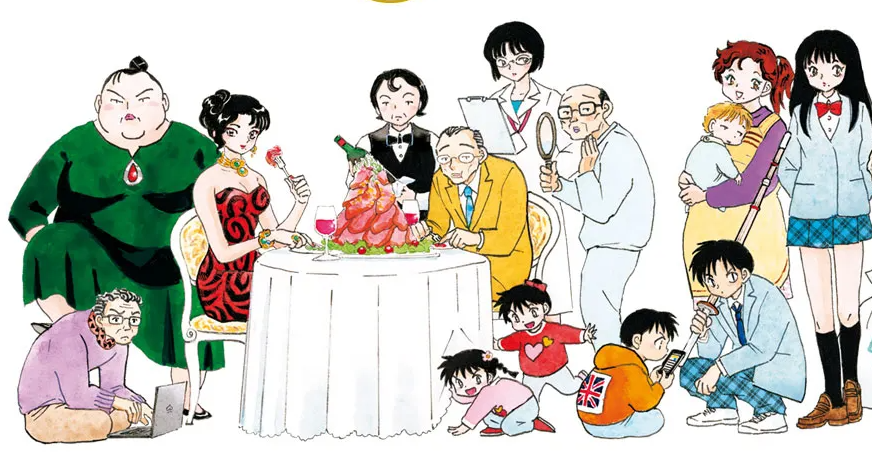

When one happens upon the name “Rumiko Takahashi,” it’s difficult not to conjure up memories of her many works, which achieved success in Italy primarily thanks to excellent television adaptations. The one who is effectively considered “The Princess of Manga” was, in fact, the mind (and especially the pen) behind the success of widely popular media franchises, both in Japan and in Italy.

Indeed, Takahashi-sensei has been able to speak to multiple generations of readers without distinction of gender or social background: older generations will remember her for the sexy sci-fi comedy Urusei Yatsura, better known in Italy as Lamù, or for the story of ordinary daily life recounted in the poignant Maison Ikkoku, which arrived on Italian television schedules under the name Cara, dolce Kyoko. The 1990s, on the other hand, were dominated by the revolution of Ranma 1/2, a true exercise in style based on the framework of shonen language, capable of mixing martial arts fights, comedy, fan service, and a human sensitivity that shines through today, as it did then, from every single panel of the long-running manga series. And then, of course, it’s hard not to mention the great success of Inuyasha in the early 2000s, whose television adaptation was for years a flagship title of the much-missed “Anime Night” on MTV and of the stable of animated products brought to Italy by the Bologna-based label Dynit.

Over time, therefore, Rumiko Takahashi has managed to speak to multiple generations without ever shaking off the consistent positive reviews that have always characterized her works, true portals to worlds so similar to Japanese daily life, yet magical and inhabited by characters so iconic that they have led her work to break every box office record both at home and abroad. If at the end of 2020 we can dive into her new, great work, arriving in Italy thanks to Star Comics (here’s our review of Mao), it’s also right to rediscover a side of the author perhaps less known to the less attentive, or simply to those who have followed the “creative from the Land of the Rising Sun” only on the occasion of her most famous serializations.

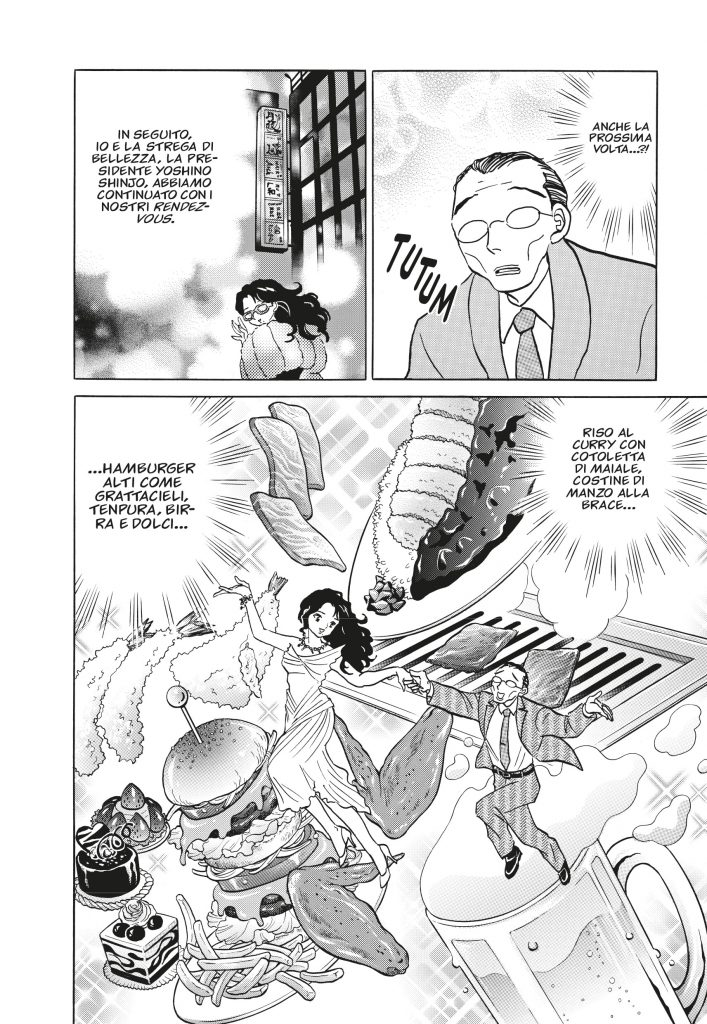

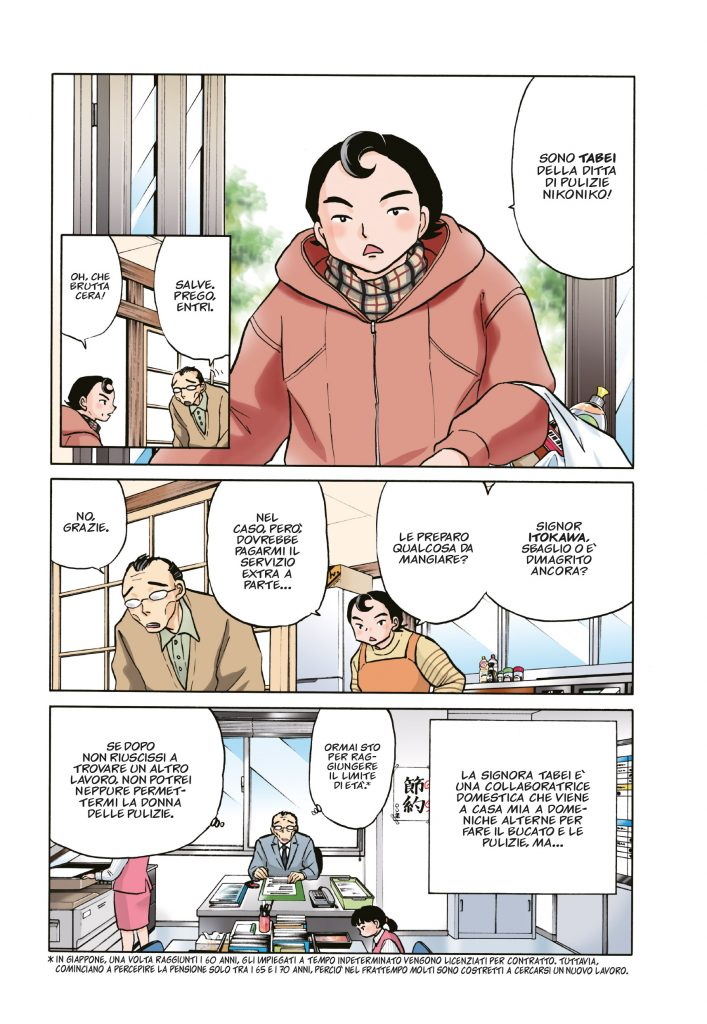

One thing is certain: Rumiko Takahashi is an excellent author even when distanced from the lighthearted and schizophrenic pace of her most famous and beloved ensemble works. Witch and Dinner (Dinner with the Witch) is one of the striking examples of what I have just stated: it is a collection of six short stories that deal with themes far removed from the “shouted” language typical of her most acclaimed productions, taking all the time necessary to clearly outline certain aspects of the daily lives of male and elderly protagonists, trapped and confused on the threshold of old age.

The ability of this author is not only measured by the renewed detail of a versatile, albeit highly recognizable, graphic style, nor by her capacity to orchestrate situations of ordinary daily life by mixing the realistic with the absurd: the secret lies entirely in the writing. Rumiko Takahashi speaks to us with complete frankness about people who have reached an age where disillusionment can only give way to alienation, monotony, and the inability to find their place in a society that no longer knows what to do with you if you are no longer recognized as an active member of the capitalist machine. The adventures of these elderly salarymen, or former ones, are united by the common thread of the female figure, explored here with extreme honesty and without any fear of being irreverent. Rumiko Takahashi’s work brought to us by Star Comics is a very straightforward fresco of a present that must come to terms with the limits that reality places before us, often shattering the illusions and dreams of youth that until then we thought guided all our steps.

It is, in short, a collection of stories that knows how to mix humor and seriousness, without failing to explain to the reader the point of view of the eternal “Him” and “Her,” men and women who flee from old age, or who simply accept their youthful mistakes by looking to the future with a smile. There is so much, so much humanity in each of the six stories that make up the work, and it is very easy to get carried away by the simple, yet effective screenplay of each of them. Stories of “extraordinary” everyday life, if you will. Without taboos or prudishness: the heroes and heroines of Witch and Dinner will surely reach your heart precisely because of their unassailable honesty, and frankly, I can only recommend reading this volume precisely by virtue of a rediscovery that, in the opinion of the writer, should be essential: separating this author from her well-known folkloric universes to get to know a frank and skilled storyteller who proves that she does not need tried and tested narrative tricks and clichés to be able to speak to the hearts of her readers.

Witch and Dinner is a recommended read especially for those who want to rediscover a well-known author like Rumiko Takahashi tackling short and simple stories. The narration is fluid and compelling, and once you start reading, it will be difficult to take your eyes off the 208 pages that make up the volume.