Bishojo Senshi Sailor Moon, or Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon, a clever mix of shoujo manga-style romance and action inspired by tokusatsu (particularly La Belle Fille Masquée Poitrine, a 51-episode Japanese TV series aired in 1990), was a multimedia project meticulously planned by Toei Animation, the publishing house Kodansha, Fumio Osano (an editor who followed and influenced the manga’s serialization), and Naoko Takeuchi, the mangaka and face traditionally credited with the entire franchise’s creation. The reality, however, is much more complex than it might seem, and the origin of the Sailor Moon project is actually attributable to a collective of authors (among whom prominent figures like Hideaki Anno, Yoji Enokido, Kunihiko Ikuhara, Ikuko Itoh, Takanori Arisawa, Junichi Sato, and Kazuhisa Takenouchi, all influential creators in the Japanese animation industry, stand out). This collective crafted a cross-media reality capable of developing in parallel and independently across multiple platforms. Sailor Moon, in every incarnation, was able to influence 90s pop culture and the production of children’s shows in the years that followed.

Sailor Moon Stars, the fifth and final season of the animated series, ultimately marked the conclusion of the franchise under Toei Animation’s stewardship. And despite what nostalgia might dictate, it did so in the most disappointing and rushed way possible, leaving fans at the mercy of plot holes and narrative lines that were merely sketched out but never truly explored. This is certainly no secret, and if one researches Japanese-language sources, the very mundane reason behind this sad truth can also be discovered: the anime no longer had the commercial pull it once did (we’re talking about a television share that reached 19.3% only during the first 123 episodes). In a prolific industry like Japanese animation, capable of producing more than 100 new animated series in a single year, it was by then perceived as a tired and uninteresting product. It’s no coincidence that for Sailor Stars, the production opted for a substantial change in staff members, with Kunihiko Ikuhara leaving the main director’s chair due to artistic differences encountered between him and Naoko Takeuchi.

UPDATE: The “Takeuchi versus Ikuhara” issue has long remained one of the great mysteries behind the production of Sailor Moon. Considering the world of Japanese PR, I doubt we will ever find a frank and honest answer to the matter. I referred to a passage from the Japanese Wikipedia page, therefore curated by native speakers, which states, “武内との確執から『SuperS』をもって東映アニメーションを退社した幾原邦彦は、二代目シリーズ構成の榎戸洋司ら少数精鋭のスタッフと株式会社ビーパパスを創設し、本シリーズのノウハウを活かした『少女革命ウテナ』『輪るピングドラム』『ユリ熊嵐』等を制作している。” – the term used is precisely “確執 kakushitsu,” which indeed means feud/antagonism. I’d be happy to be proven wrong by more authoritative sources: articles found online merely state that “this doesn’t emerge from official interviews,” but I would be surprised if it were otherwise, given that in Japan, it’s etiquette never to speak harshly or ungratefully about companies one has worked for in the past. The same, of course, applies to colleagues.

The director, however, ended up producing an animated series, Shojo Kakumei Utena, with two lesbian-coded protagonists based on the template of two characters who appeared in the Toei series: Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune.

The changes in production led to substantial modifications in the show’s presentation. The historic opening “Moonlight Densetsu” was dropped to be replaced with the more modern “Sailor Star Song”; the TV series logo was changed to highlight the title “Sailor Stars” in contrast to the historic “Bishojo Senshi Sailor Moon” – a necessary act to make the audience believe it was something genuinely new – and character design and screenwriting saw the debut of new artists with styles and authorial urgencies that substantially contrasted with the imprint of those who preceded them. In short, Sailor Moon Stars, for many reasons, did not convince the Japanese audience, and perhaps it is also for this reason that it became the shortest season, to the point of not even being followed by a film adaptation (unlike the previous seasons) or TV specials dedicated to individual characters.

Although it is difficult to find confirmation, it has been hypothesized by enthusiasts and professionals in the sector that the television series was at some point internally canceled by Toei Animation itself, thus forcing the artistic staff working on Sailor Stars to conclude the story as quickly as possible and with the elements they had introduced up to that point. The decision must have been made suddenly since one of the narrative cornerstones of the story, namely the mystery behind Chibi-Chibi’s identity, was blatantly rewritten at a later stage, to the point of making the clues and elements of clear foreshadowing scattered throughout the episodes aired up to that point completely irrelevant.

That being said, we know for certain that Naoko Takeuchi and her editor were in charge of creating concepts, drafts, and designs for the main characters of the series, a role not unlike the one they had held up to that point for the previous four seasons.

In its second part, the printed version of Sailor Stars introduces several characters who never appeared in the animated show, most likely due to the axe with which Toei Animation decided to cut the show in half. Until today, this had been a sort of theory floating around the fandom, or even an “open secret” of the entire Japanese animation industry, but today I can present evidence that would give greater credibility to this scenario.

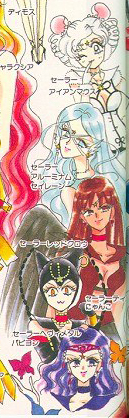

During a recent live stream on Immanuel Casto’s channel, a musical performer and former President of Mensa Italy, Marco Albiero stated that he had viewed production material from Sailor Moon Stars that would prove Toei Animation’s intention to translate a character who only appeared in the manga into the animated series. Albiero is an Italian illustrator who works for Toei Animation as the official illustrator of Sailor Moon (and other Japanese animation brands), and clearly, until today, these official sources he refers to had never been publicly discussed. The revelation comes from the illustrator’s own words, who explains that he came into possession of settei (character sheets) that would confirm that the animated series should have also included Sailor Heavy Metal Papillon in the Sailor Stars story. This means that the animators and the official character designer of Toei Animation worked on this character, producing reference material for the animators that was not then used during the production of the animated series.

This Sailor Guardian was none other than the fifth member of the Animamates, the servants of the villain of the fifth and final arc of the saga, Sailor Galaxia. If this is true, and given the reliability of the source it would be difficult to think otherwise, one can only imagine what other characters could have appeared in the animated adaptation produced between 1996 and 1997: after all, today we know that a character prepared for the episodes was indeed canceled (and with her, probably an entire narrative arc of the season, given the generous amount of character development given to each of the four villains).

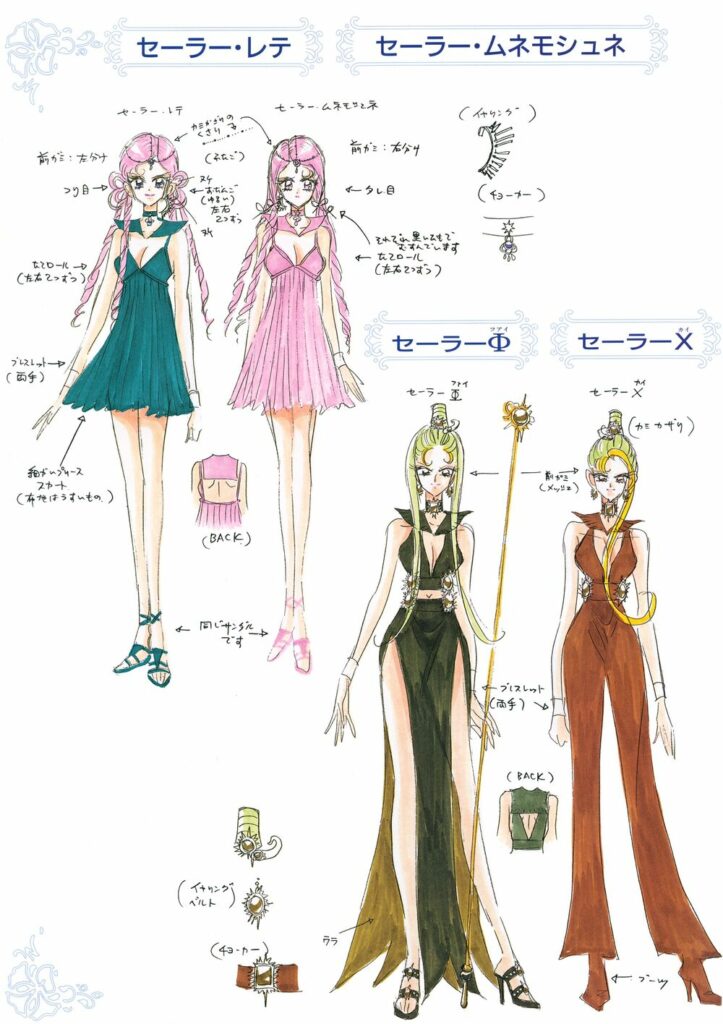

Not only the Animamates group: the manga names and shows several guardians entirely absent from the animated series, such as Sailor Chaos, Sailor Kakyuu, Sailor Chuu, Sailor Coronis, Sailor Mermaid, Sailor Mau, Sailor Cocoon, Sailor Lethe, Sailor Mnemosyne, Sailor Phi, and Sailor Chi.

Given the recent confirmation of the arrival of a new animated adaptation of Sailor Moon dedicated to the Stars arc, it is practically confirmed that all these characters will see an animated translation in the form of a TV series or an animated film intended for theaters. What is certain is that until today, neither the recent reboot, Crystal, nor the two-part animated film, Eternal, have been able to offer a good animated transposition of the already debatable original material drawn and written by Naoko Takeuchi and her editor.

It would have been interesting to see how the members of Toei Animation’s production would have introduced and rewritten these characters, perhaps even revising their character design for the occasion, but unfortunately, the entertainment industry is ruthless.

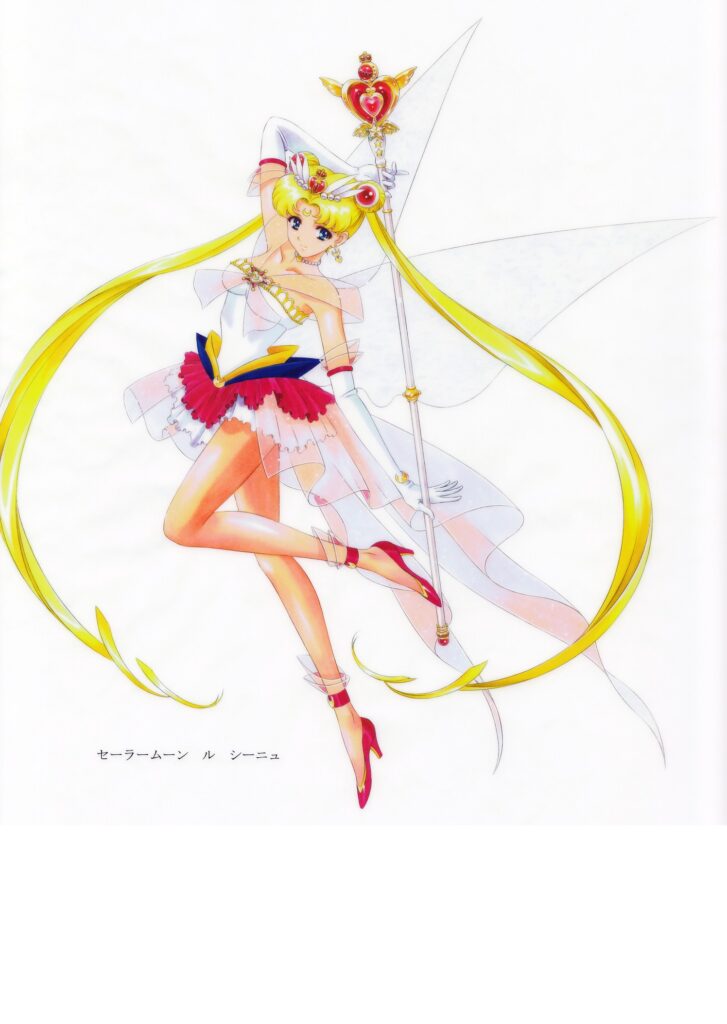

In closing, I’ll leave a final tidbit regarding the production of the historical anime: Youichi Fukano, the historic illustrator of Sailor Moon (the cover of this article is his), recently unveiled a preliminary design that should have replaced the winged form design of Eternal Sailor Moon in the historical anime. This transformation, called “Sailor Moon La Cygne,” shows elements halfway between the sailor-style outfit of Super Sailor Moon and the regal elements of Princess Serenity’s dress. In the end, Toei Animation decided to follow Naoko Takeuchi’s design, considered by many to be “too much” due to the gigantic angel wings mounted on the protagonist’s back, but I wonder if the public would have appreciated this ballerina-themed concept. Moreover, even the outfits of the other Sailor Guardians did not see the changes made in the manga version during the Stars arc in the anime, and this became a long-standing point of debate in the fandom (and meanwhile, I still can’t fathom those spherical shoulder pads).